Imagine piecing together the lives of our distant ancestors through seemingly insignificant objects. A recent study published in Scientific Reports offers a fascinating glimpse into this process, shedding light on the woodworking practices of early humans 300,000 years ago.

Researchers from the University of Tübingen and the Senckenberg Center for Human Evolution and Paleoenvironment (SHEP) meticulously analyzed a collection of tiny flint flakes unearthed at the Lower Paleolithic site of Schöningen in Lower Saxony, Germany. These unassuming flakes, often discarded as mere byproducts of tool creation, hold a wealth of information when examined with a multidisciplinary approach.

The flakes, numbering 57 alongside three bone implements used for tool resharpening, were discovered near the skeleton of a long-deceased Eurasian straight-tusked elephant at a former lakeshore. “These finds provide evidence that early humans, likely Homo heidelbergensis or early Neanderthals, were present in the vicinity of the elephant carcass,” explains Dr. Jordi Serangeli, leading archaeologist for the Schöningen excavations. He further highlights the significance of the location, situated roughly two meters below the famous site where the world’s oldest spears were unearthed.

Dr. Flavia Venditti, lead author of the study and researcher at Tübingen, emphasizes the importance of seemingly ordinary objects in understanding Stone Age life. “While large tools like knives and scrapers might appear more significant, even microscopic stone chips can offer valuable insights into the lives of our ancestors, particularly when considered within the broader context of available evidence,” she explains.

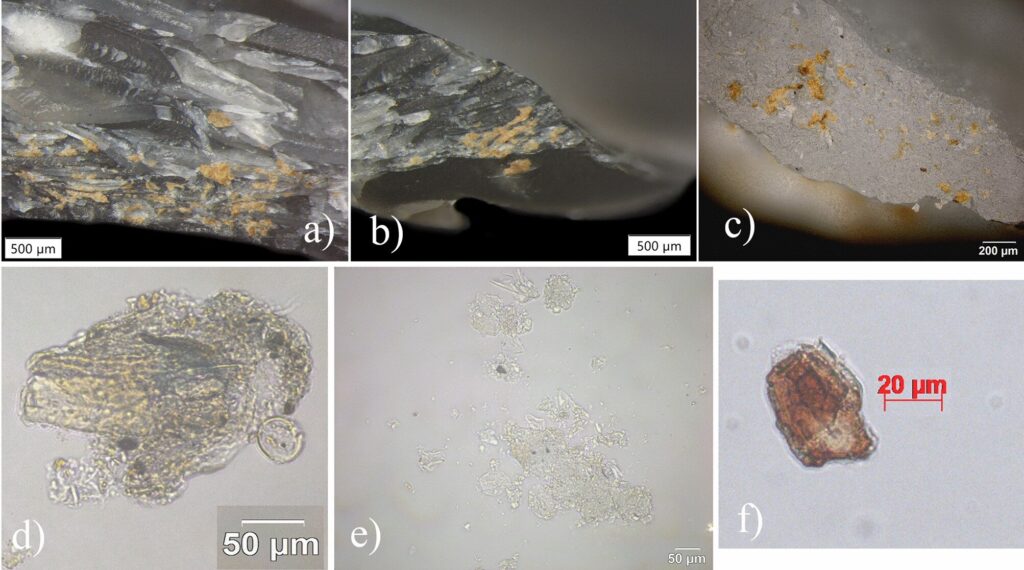

The analysis revealed that most of the flakes were smaller than a centimeter and originated from knife-like tools, discarded during the resharpening process. However, their minute size doesn’t diminish their significance. “Through a combination of techniques, including technological and spatial analysis, residue examination, and methods drawn from experimental archaeology, we were able to extract a wealth of information from these stone chips,” says Dr. Venditti.

Intriguingly, 15 of the flakes displayed telltale signs of use associated with working fresh wood. Microscopic examination revealed traces of wood residue clinging to the former tool edges. This discovery, coupled with the identification of micro wear marks on a natural flint fragment – suggesting its use in cutting fresh animal tissue, possibly during the butchering of the elephant – paints a vivid picture of how these tools were employed.

Professor Nicholas Conard of Tübingen and head of the Schöningen research project underscores the significance of this study. “It demonstrates how meticulous analysis of use-wear traces and microscopic residues can unlock information from seemingly insignificant artifacts. This is the first instance where such comprehensive results have been obtained from 300,000-year-old resharpening flakes,” he explains. He further emphasizes the crucial role of careful handling throughout the excavation and analysis process to preserve the integrity of these delicate artifacts.

The ongoing research at Schöningen, a collaborative effort between the University of Tübingen, the Senckenberg Nature Research Society, and the State Heritage Office of Lower Saxony, serves as a testament to the power of meticulous analysis. By delving into the details, even tiny flakes of flint can offer invaluable insights into the lives and ingenuity of our distant ancestors.

Source: Universitaet Tübingen