Schöningen, a region in Lower Saxony, Germany, continues to unveil its secrets from a bygone era. Renowned for its rich archaeological deposits dating back 300,000 years, Schöningen has recently yielded a remarkable discovery – an almost complete skeleton of a Eurasian straight-tusked elephant (Palaeoloxodon antiquus). This exceptional find sheds light on the lives of these ancient giants and the environment they inhabited.

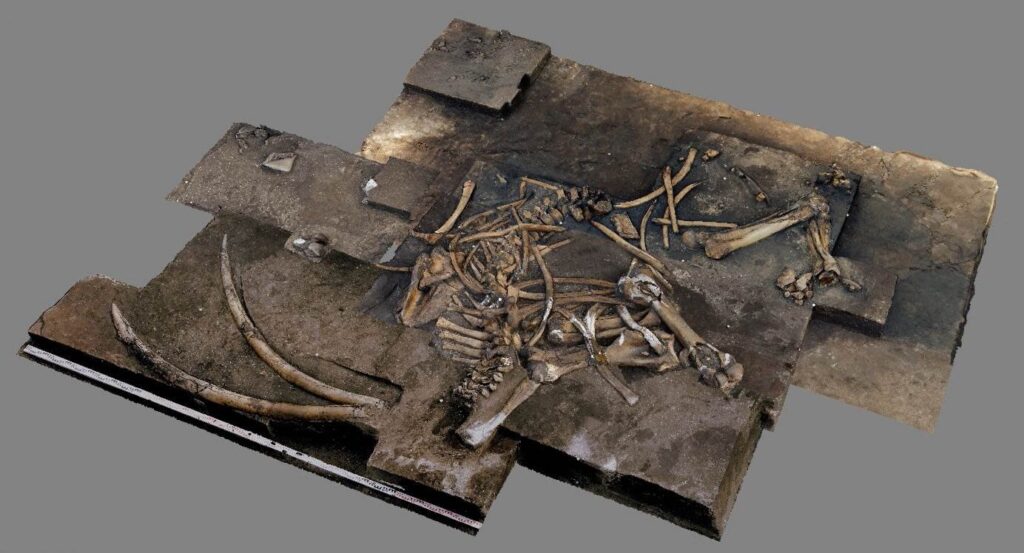

Unearthed by archaeologists from the Senckenberg Centre for Human Evolution and Palaeoenvironment at the University of Tübingen, in collaboration with the Lower Saxony State Office for Heritage, the elephant skeleton lay remarkably well-preserved in water-saturated sediments on the former western lakeshore. “We found both 2.3-meter-long tusks, the complete lower jaw, numerous vertebrae and ribs,” explains Dr. Jordi Serangeli, head of the excavation. “Even the delicate hyoid bones were present,” he adds, highlighting the exceptional preservation.

The analysis suggests the elephant was an older female with worn teeth, estimated to have stood at a shoulder height of 3.2 meters and weighing a staggering 6.8 tonnes – considerably larger than today’s African elephant cows, according to archaeozoologist Dr. Ivo Verheijen.

While the cause of death remains undetermined, researchers believe old age is the most likely culprit. Supporting this theory is the discovery of the remains near water, a common behavior observed in ailing elephants. Furthermore, the lack of evidence suggesting human intervention points towards a natural demise.

However, the presence of the carcass undoubtedly presented an opportunity for the hominins of the time, likely Homo heidelbergensis. Intriguingly, flint flakes and tools used for knapping were found amongst the elephant bones. Microscopic analysis revealed traces of resharpening activity on these tools, suggesting the location served as a workshop for early humans. “The Stone Age hunters probably cut meat, tendons and fat from the carcass,” explains Dr. Serangeli, hinting at the potential utilization of this abundant resource.

While the elephant’s death wasn’t necessarily caused by human hunting, its remains likely provided a valuable source of food and materials for early humans. Researchers emphasize that these early hominins, despite being skilled hunters, wouldn’t have actively targeted such large and potentially dangerous prey. “Straight-tusked elephants were a part of their environment, and the hominins knew that they frequently died on the lakeshore,” says Dr. Serangeli.

The discovery adds to a growing body of evidence suggesting a potential connection between elephants and early human settlements. Footprints discovered 100 meters from the excavation site offer further clues. These tracks, identified by Dr. Flavio Altamura as belonging to a small herd of adult and younger elephants, suggest the area served as a frequented corridor for these giants.

Schöningen’s rich tapestry extends beyond the recent elephant discovery. Previous excavations have unearthed a wealth of information about the local ecosystem 300,000 years ago. The climate during this period, known as the Reinsdorf interglacial, mirrored that of today, but the landscape teemed with a remarkable diversity of wildlife. Lions, bears, sabre-toothed cats, rhinoceroses, wild horses, and various bovids shared the habitat with the elephants, creating an environment reminiscent of modern Africa.

Schöningen has also yielded some of Europe’s oldest fossil finds of aurochs (extinct wild cattle) and water buffalo, alongside the world’s oldest and best-preserved wooden hunting weapons – ten spears and a throwing stick. These discoveries, combined with the recent elephant skeleton, paint a vivid picture of the lives of Homo heidelbergensis and the environment they inhabited.

Further research is underway at various universities to delve deeper into the environmental and climatic conditions surrounding the elephant’s demise. As excavations continue, Schöningen promises to unveil even more secrets, offering a captivating glimpse into a world dominated by giants.

Source: Universitaet Tübingen