In recent years, archaeological research has unveiled intriguing evidence of permanent body modification practices among the Norse and Vikings of the Viking Age. Among the latest discoveries is the investigation into three Viking Age women from the Baltic Sea island of Gotland who underwent skull elongation, shedding new light on the fascinating tradition of body modification within this ancient culture.

The research, published in the journal “Current Swedish Archaeology” by Matthias Toplak and Lukas Kerk, has identified approximately 130 individuals, predominantly men, with horizontal grooves carved into their teeth, with a notable concentration on Gotland. While various interpretations of these dental modifications have been proposed, ranging from indications of slave status to symbols of warrior elites, the researchers suggest they may have functioned as identity markers within a closed group of traders.

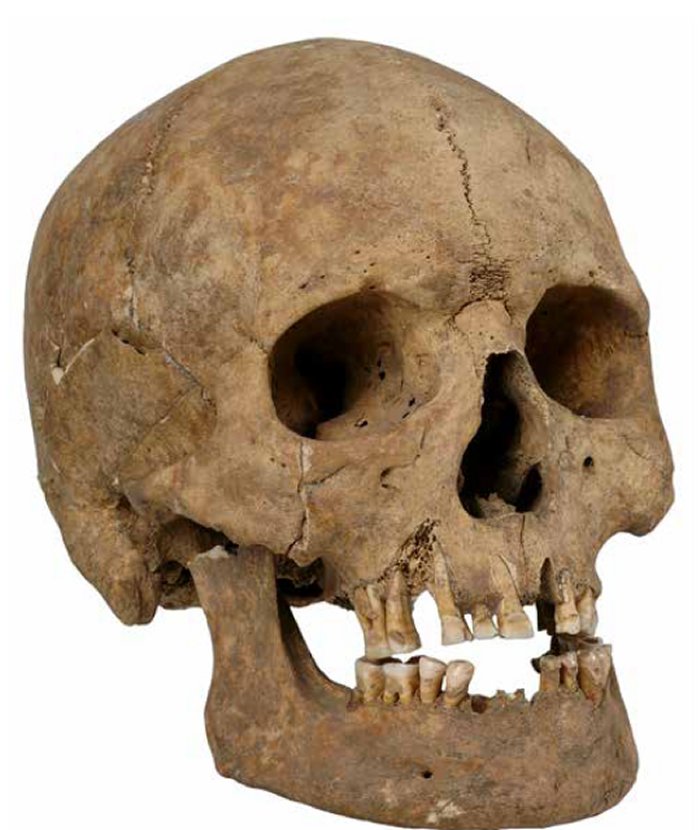

Remarkably, artificial cranial modifications in the Viking Age are known from just three female individuals from Gotland. Dating back to the late eleventh century, these women were laid to rest in different locations across the island, their elongated skulls giving them a distinctive appearance.

Further analysis reveals intriguing details about these women: one was aged between 25 and 30 at the time of her passing, while the other was between 55 and 60 years old. Unlike dental modifications, these cranial alterations appear to be foreign to Scandinavian Viking culture, with similar cases dating from the 9th to the 11th century AD found in Eastern Europe, suggesting a possible origin in that region.

The presence of these women with modified skulls raises questions about the interaction between Gotland society and this foreign practice upon their arrival in Scandinavia. The authors speculate on two possible scenarios: either the women were born in southeastern Europe, possibly as the children of Gotlandic or East Baltic traders, and underwent skull modifications there, or the modifications were performed on Gotland or in the eastern Baltic, indicating a cultural adoption previously unknown in the Scandinavian Viking Age.

Despite the uncertainty surrounding the origins of skull modification on Gotland, the elaborately decorated tombs of these women, adorned with jewelry and other accessories typical of Gotland women’s clothing, suggest they were accepted and integrated into the local community. While their religious affiliations remain unknown, Toplak and Kerk propose they were laid to rest within a Christian framework, adding another layer of complexity to the cultural tapestry of Viking Age Scandinavia.