In a remarkable discovery, a team of biomedical and medicinal specialists from the University of Milan, in collaboration with a colleague from Foundation IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico di Milano, has uncovered evidence of cocaine use in Europe dating back to the 17th century. Their groundbreaking findings, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, reveal that at least two individuals were using cocaine nearly 200 years before it became widely recognized as a recreational drug in Europe.

Historical Context of Cocaine Use

Cocaine, derived from the coca plant, has a long history of use, particularly in South America. Indigenous peoples in western regions of the continent have chewed coca leaves for thousands of years to experience the plant’s stimulant effects. The active ingredient in these leaves, which would later be refined into cocaine hydrochloride in the 19th century, provided both a physical and psychological boost to users. With the advent of more refined production techniques, cocaine became known as a powerful psychoactive drug and gained popularity across Europe and other parts of the world.

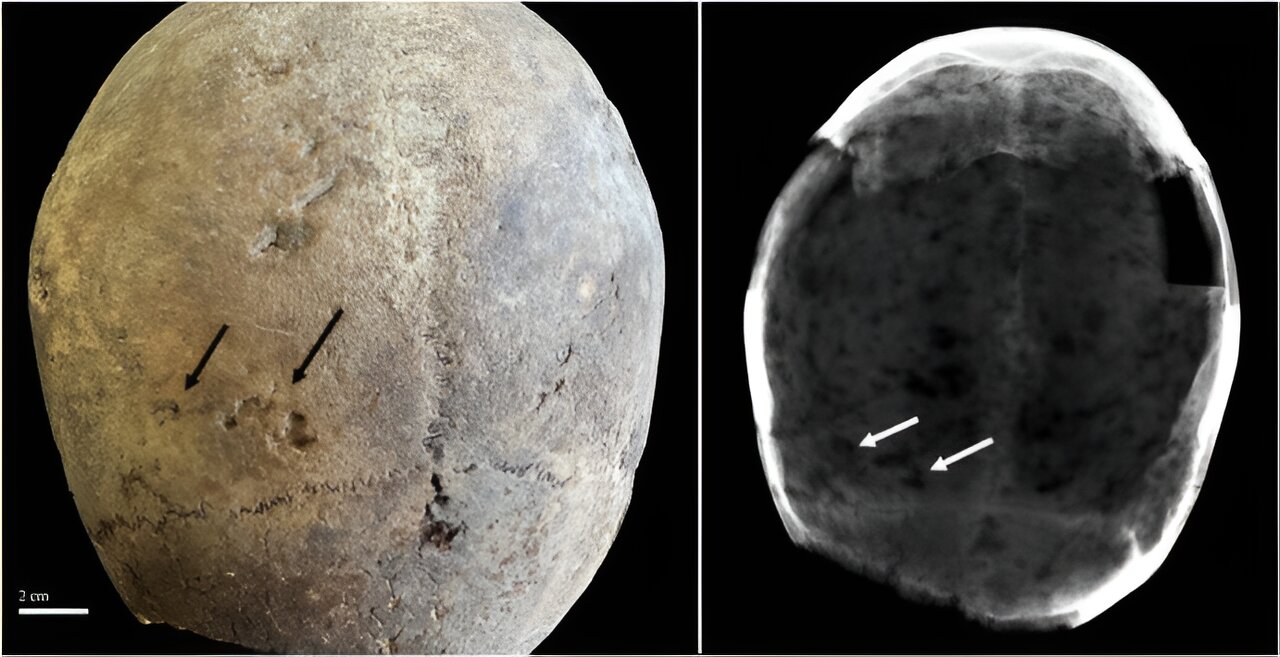

However, the new study conducted by the Milanese team suggests that the use of coca leaves in Europe occurred much earlier than previously documented. Their research focuses on the preserved brains of two individuals discovered in a crypt in Milan, which served as a burial site for those who died at the nearby Ospedale Maggiore, one of the most prominent hospitals of the era.

The Discovery

The crypt, known as Ca’ Granda, was used throughout the 17th century as a final resting place for many of Milan’s deceased, particularly those who were less affluent. Among the remains, researchers found two mummified bodies that showed surprising signs of coca leaf consumption. By analyzing the brain tissue of these individuals, the team identified the presence of alkaloids unique to the coca plant, indicating that these people had ingested coca leaves, likely by chewing them as was traditionally done in South America.

This discovery challenges the conventional understanding of when and how cocaine use spread beyond its indigenous roots in the Americas. Prior to this study, the general consensus was that cocaine use in Europe did not become prevalent until the 19th century, following the establishment of trade routes and the refinement of coca leaves into the more potent cocaine powder. However, the presence of coca alkaloids in the remains from the 17th century suggests that coca leaves, or possibly a crude form of the drug, were available and used in Europe much earlier.

Implications of the Findings

One of the most intriguing aspects of this discovery is the social and economic implications it carries. The individuals in question were buried in a manner suggesting they were of lower socioeconomic status, which implies that coca leaves might have been relatively accessible and inexpensive at the time. This raises questions about the extent of coca leaf use in Europe during the 17th century and whether it was more widespread than previously thought.

Additionally, the research team examined historical pharmacological records from Ospedale Maggiore and found no evidence that coca leaves or cocaine were used for medicinal purposes in the hospital during that period. This suggests that the coca leaves were likely used for their psychoactive effects rather than for any therapeutic benefit. The absence of medicinal use in official records further supports the idea that these individuals were using coca leaves recreationally, possibly to cope with the harsh realities of their lives.