The discovery and analysis of ancient human remains provide invaluable insights into our shared history, shedding light on the migrations, interactions, and cultural developments of early human societies. Among these, the Aurignacians, a culturally sophisticated group that thrived in Europe around 40,000 years ago, have long intrigued researchers. Now, a collaborative effort involving researchers from Tel Aviv University, the Israel Antiquities Authority, and Ben-Gurion University has unveiled fascinating revelations about the Aurignacians who ventured into the Levant millennia ago.

Originating in Europe approximately 43,000 years ago, the Aurignacian culture is renowned for its rich material culture, encompassing bone tools, artifacts, jewelry, musical instruments, and captivating cave paintings. For decades, scholars have debated the fate of the Neanderthals in relation to the arrival of modern humans in Europe, speculating on scenarios ranging from violent conflict to peaceful coexistence. Recent genetic studies have provided compelling evidence that rather than facing extinction, Neanderthals interbred with incoming modern human populations, contributing to the genetic diversity of our ancestors. The latest research adds another layer to this narrative, offering fresh insights into the movements and compositions of ancient populations.

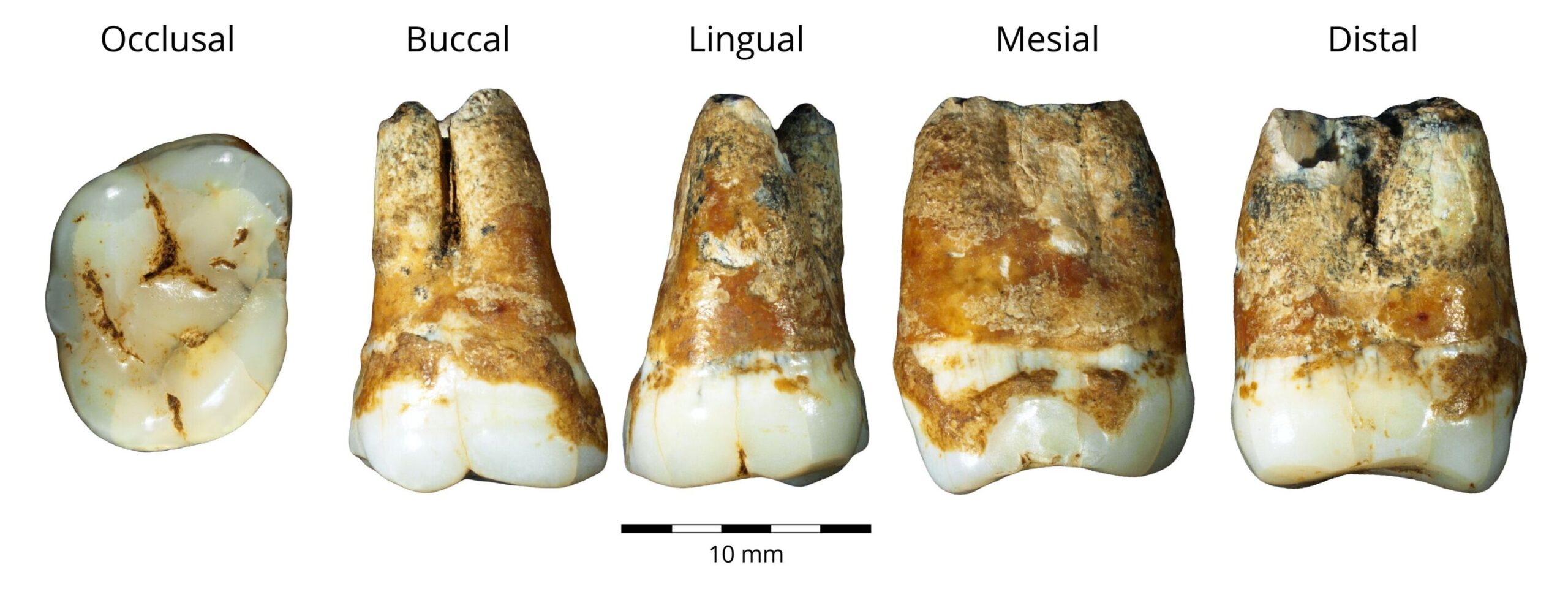

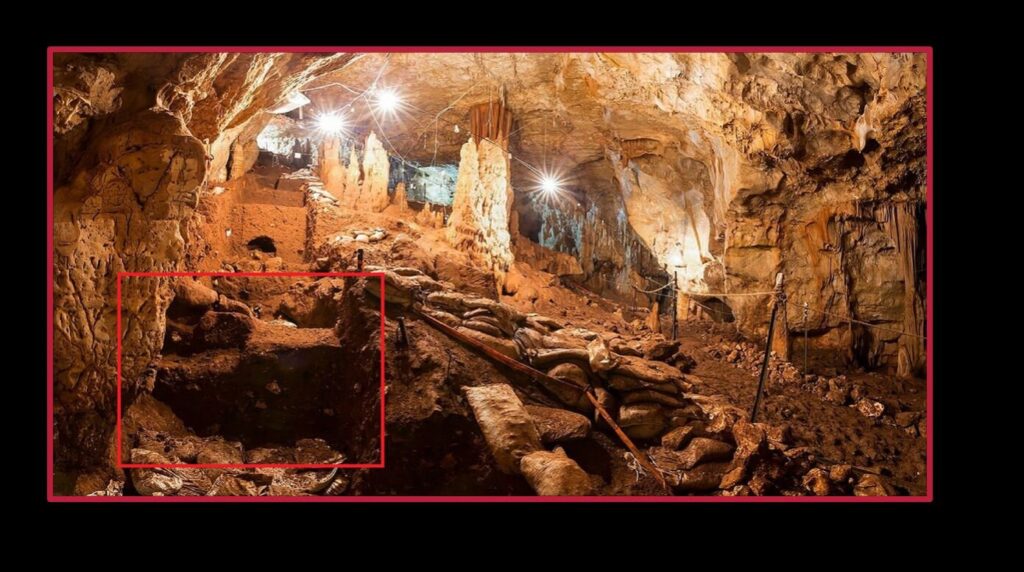

The focal point of this study lies in the examination of six human teeth recovered from Manot Cave in the Western Galilee. Dr. Rachel Sarig, affiliated with TAU’s School of Dental Medicine and the Dan David Center for Human Evolution and Biohistory Research, collaborated with Dr. Omry Barzilai of the Israel Antiquities Authority, along with international colleagues, to conduct meticulous analyses of these dental specimens. Unlike bones, teeth possess remarkable preservation potential due to their enamel composition, making them invaluable sources of genetic and morphological information.

Employing state-of-the-art techniques such as micro-CT scanning and 3-D analysis, the researchers scrutinized the dental morphology of the specimens. The results yielded intriguing revelations: while two teeth exhibited characteristic features of Homo sapiens, one tooth displayed distinct Neanderthal traits, and another showcased a hybrid morphology combining Neanderthal and modern human characteristics. This amalgamation of features, previously observed only in early Paleolithic European populations, hints at a shared ancestral lineage.

The findings not only confirm the presence of Aurignacian individuals in the Levant approximately 40,000 years ago but also unveil the complex composition of these ancient populations. Contrary to previous assumptions, the Aurignacians in the Levant comprised a blend of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens, highlighting the dynamic interplay between different hominin groups during this pivotal period of human history.

Furthermore, the researchers’ meticulous dental analyses provide crucial insights into the genetic makeup and migratory patterns of ancient populations. By tracing the origins of these individuals to Europe, the study underscores the interconnectedness of prehistoric human societies and the fluidity of population movements across geographical boundaries. The presence of Aurignacian populations in the Levant for a relatively brief period, estimated at 2,000-3,000 years, raises intriguing questions about their interactions with local Neanderthal populations and the factors contributing to their eventual disappearance from the region.

Prof. Israel Hershkovitz, head of the Dan David Center, emphasizes the significance of these findings in unraveling the mysteries surrounding ancient populations. Prior to this study, the dearth of human remains from this period in Israel left a significant gap in our understanding of the region’s prehistory. The identification of Aurignacian individuals in the Levant not only enriches our knowledge of early human migrations but also highlights the cultural contributions of these enigmatic populations.

The research was published in the Journal of Human Evolution on October 11.