A groundbreaking study, led by scientists from the Francis Crick Institute, University of Oxford, and University of Vienna, sheds new light on the early history of dogs. By analyzing the DNA of ancient canines, the research team unveils a surprising level of diversity among dogs as early as 11,000 years ago, just after the Ice Age.

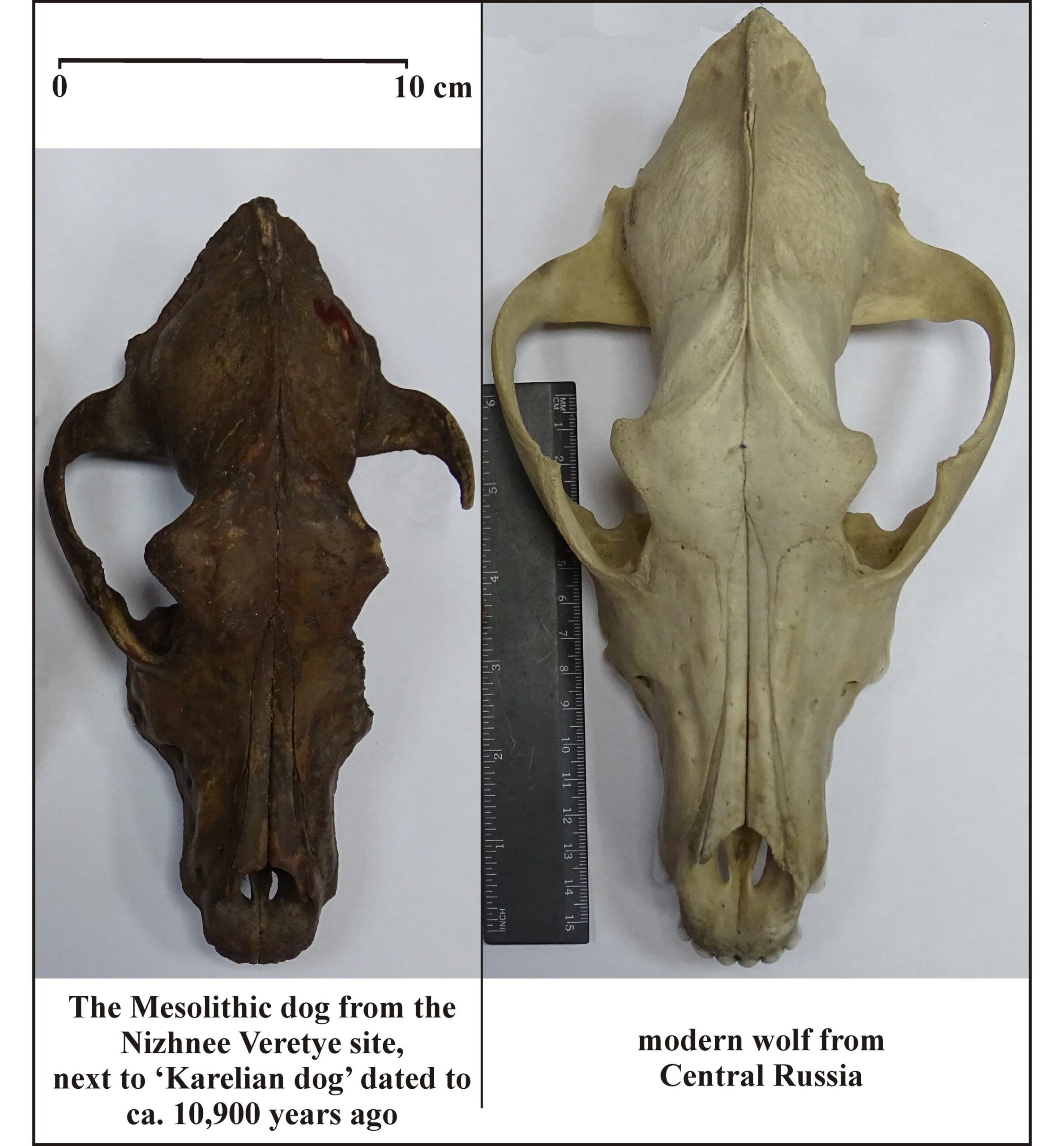

The research, published in the prestigious journal Science, involved sequencing DNA from 27 ancient dogs spanning Europe, the Near East, and Siberia. These canine specimens, some dating back nearly 11,000 years, reveal the existence of at least five distinct dog types with unique genetic ancestries. This finding challenges previous assumptions and suggests that dog diversification began much earlier than anticipated, predating the domestication of any other animal.

“The incredible variety we see in modern dogs walking beside us today has roots that stretch back to the Ice Age,” explains Dr. Pontus Skoglund, lead author and head of the Ancient Genomics laboratory at the Crick Institute. “By the end of this glacial period, dogs had already established a widespread presence across the northern hemisphere.”

The power of ancient genomics lies in its ability to unlock the secrets of the past through analysis of DNA extracted from skeletal remains. This study offers a unique window into the evolutionary changes that shaped dog lineages over thousands of years.

The research team observed a fascinating process of dog lineage mixing and migration over the past 10,000 years, ultimately leading to the vast array of dog breeds we know today. For instance, early European dogs exhibited remarkable diversity, seemingly originating from two distinct populations: one with Near Eastern ancestry and another linked to Siberian dogs. However, this European diversity has vanished, leaving modern European canines with a significantly narrower genetic makeup.

“Looking back just a few thousand years, Europe boasted an incredibly diverse dog population,” comments Dr. Anders Bergström, lead author and postdoctoral researcher at the Crick Institute. “While today’s European dogs come in a stunning array of shapes and sizes, their genetic heritage stems from a very limited portion of the once-existing diversity.”

The study delves deeper, comparing the evolutionary trajectories of dogs with human history, migration patterns, and changing lifestyles. The researchers observed instances where dog and human histories mirrored each other, suggesting a connection between human migration and canine dispersal. However, intriguing discrepancies also emerged. The loss of diversity in European dogs, for example, appears to be a consequence of a single dog lineage outcompeting and replacing existing populations – an event with no parallel in human history.

“Dogs hold a special place as our oldest and closest animal companions,” remarks Dr. Greger Larson, co-author and Director of the Palaeogenomics and Bio-Archaeology Research Network at the University of Oxford. “Ancient dog DNA provides invaluable insights into the immense depth of our shared history, ultimately helping us pinpoint the origins and context of this remarkable relationship.”

Dr. Ron Pinhasi, co-author and group leader at the University of Vienna, emphasizes the transformative power of ancient DNA research. “Just as it has revolutionized our understanding of human ancestry, ancient DNA is now doing the same for dogs and other domesticated animals. Studying our animal companions unlocks a new layer within the grand narrative of human history.”

While this research offers significant advancements in our understanding of early dog populations and their interactions with humans, many questions remain unanswered. The quest to pinpoint the exact location and cultural context of dog domestication continues to drive research efforts, promising even more fascinating discoveries about our canine companions.

Source: The Francis Crick Institute