Archaeologist Sue O’Connor, from The Australian National University (ANU), unearthed the world’s oldest known fishhooks associated with a burial on Alor Island, northwest of East Timor.

These meticulously placed artifacts, dating back a staggering 12,000 years to the Pleistocene era, redefine our understanding of gender roles in fishing and shed light on the development of fishing technology.

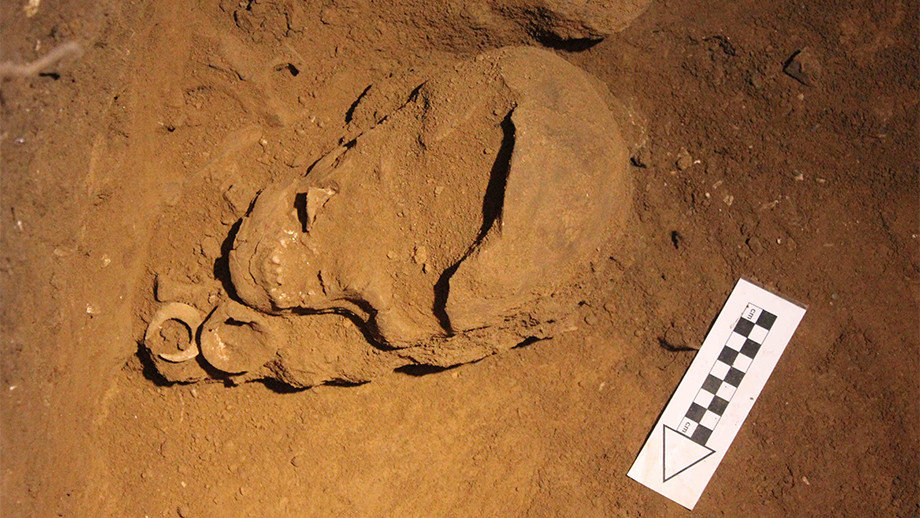

Five intricately crafted fishhooks were found carefully arranged under the chin and around the jaw of a female skeleton. This placement suggests a deep connection between the deceased and fishing, potentially indicating that fishing equipment held symbolic significance in the afterlife for this ancient community.

“The discovery turns on its head the theory that most fishing activities on these islands were carried out by men,” explains Professor O’Connor. “The presence of these fishhooks with a female burial suggests women may have played a more prominent role in fishing than previously believed.”

This find significantly predates other known burials with fishing equipment. Previously, the oldest such discovery was in Siberia’s Mesolithic Ershi cemetery, where fishhooks were found alongside a 9,000-year-old burial. In maritime environments, burials with fishhooks, like those found in Oman (around 6,000 years old), primarily featured rotating pearl shell hooks.

While older fishhooks – up to 22,000 years old – have been unearthed in Japan, Europe, and East Timor, they were not associated with burial practices.

The Alor Island find offers further intrigue as it reveals two distinct types of fishhooks: J-shaped hooks and four circular rotating hooks made from seashells. The presence of these rotating hooks, so early on a remote island, suggests a fascinating possibility.

“The resemblance of these Alor hooks to rotating hooks found across vast geographical regions – Japan, Australia, Arabia, and even the Americas – hints at independent invention,” proposes Professor O’Connor. “These communities, despite geographic isolation, may have developed similar technology due to its effectiveness in their specific environments, rather than through cultural exchange.”

Professor O’Connor’s groundbreaking research, published in the prestigious journal Antiquity, not only rewrites the narrative around gender roles in fishing but also compels us to reconsider the independent ingenuity of early fishing communities across the globe. The discovery serves as a powerful reminder that even the simplest tools can hold profound cultural and symbolic significance, offering a glimpse into the lives and beliefs of our distant ancestors.

Source: Australian National University