Archaeologists from the Australian National University (ANU) have unearthed a remarkably well-preserved child burial dating back an astonishing 8,000 years.

This unique find, the first of its kind from the early mid-Holocene period in the region, offers invaluable insights into how these ancient communities treated their deceased children. Dr. Sofia Samper Carro, lead researcher on the project, explains the significance of the discovery: “Child burials are very rare, especially from this time period. We have many examples from the past 3,000 years, but this complete burial from the early Holocene period fills a critical gap in our knowledge.”

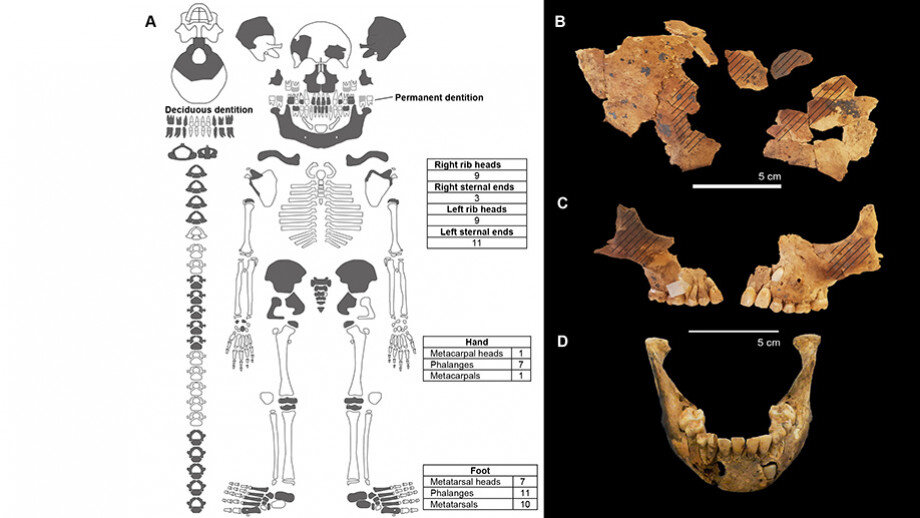

The meticulously laid-to-rest child, estimated to be between four and eight years old at the time of death, was adorned with ochre pigment on their cheeks and forehead – a potential indicator of a ceremonial burial. An ochre-colored cobble stone placed beneath the head further suggests a deliberate and respectful ritual.

However, the burial also presents a fascinating anomaly. The child’s arm and leg bones were conspicuously absent, suggesting their removal before interment. “This practice of removing long bones has been documented in adult burials from a similar period in Java, Borneo, and Flores,” Dr. Samper Carro explains, “but it’s the first time we’ve encountered it in a child’s burial.” The purpose behind this ritualistic removal remains a mystery, likely linked to the belief systems of these ancient people.

While the child’s skeleton suggests an age range of four to five years old, dental analysis points towards a possible age of six to eight. This discrepancy has piqued the researchers’ interest. “We’re planning further paleo-health research to understand if this difference is due to diet, environmental factors, or even potential genetic isolation on the island,” Dr. Samper Carro says.

Her prior research on Alor revealed similarly small adult skulls, leading to a possible dietary connection. “These hunter-gatherers likely relied heavily on marine resources,” she explains. “There’s evidence to suggest an overdependence on a single food source can lead to protein saturation, mimicking malnutrition and affecting growth.” However, the possibility of including tubers and other terrestrial resources in their diet is also being explored.

The researchers plan to compare this unique child burial with adult burials from the same period found at the site. This comparative analysis, outlined in their paper “Burial practices in the early mid-Holocene of the Wallacean Islands: A sub-adult burial from Gua Makpan, Alor Island, Indonesia” published in Quaternary International, aims to build a clearer chronology of burial practices in the region between 12,000 and 7,000 years ago – a period shrouded in mystery until now.

The paper, “Burial practices in the early mid-Holocene of the Wallacean Islands: A sub-adult burial from Gua Makpan, Alor Island, Indonesia,” is published in Quaternary International.

Source: Australian National University