Researchers from China, Singapore, and the U.S. have made a groundbreaking discovery in northeastern China, pushing back the timeline for a fascinating cultural practice – cranial modification. Their findings, published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology, unveil evidence of some of the earliest examples of this practice at a site called Houtaomuga, shedding light on a tradition shrouded in mystery.

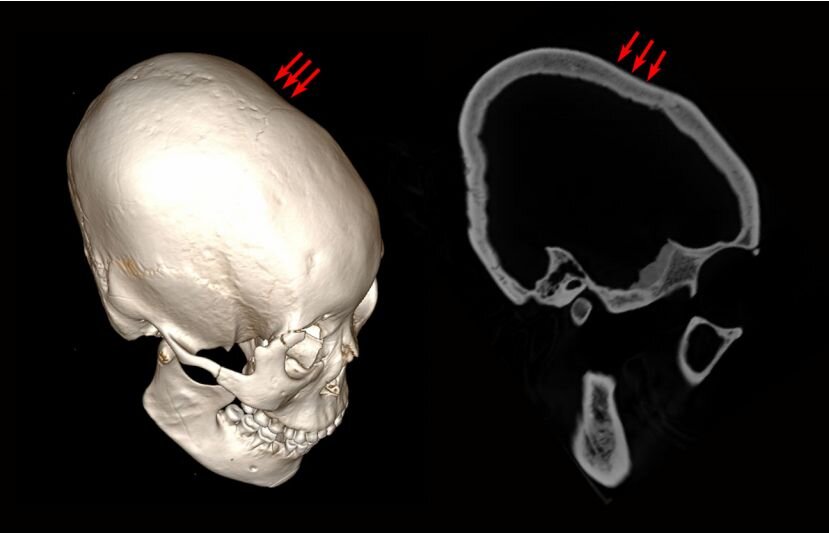

Cranial modification involves intentionally altering the shape of a skull, typically during infancy when the bones are soft. This was achieved by binding the head with materials like cloth or wooden boards. While the reasons behind this practice remain unclear across different cultures, some anthropologists theorize it served as a social marker, distinguishing members of the elite or a specific social group.

The Houtaomuga site, believed to be an ancient Chinese tomb, was excavated by archaeologists between 2011 and 2015. Interestingly, the tomb held 25 skeletons spread across a 7,000-year period, ranging from 12,000 to 5,000 years ago. Notably, 11 of these skeletons displayed evidence of intentional cranial modification. This diverse sample included four adult males, one adult female, and several children. There were no apparent gender biases in the practice.

While the researchers haven’t found definitive clues about the specific binding techniques used, they theorize that cranial modification at Houtaomuga likely served as a status symbol. This is based on the presence of burial artifacts, such as pottery, found alongside some of the modified skulls, often associated with wealth or high social standing.

The team’s work doesn’t end here. They plan to continue exploring the area surrounding Houtaomuga, searching for additional tombs that might hold further evidence of this ancient cranial modification practice. Unearthing more examples could provide crucial insights into the motivations behind this tradition and its potential role in shaping early Chinese society.

This discovery not only rewrites the timeline for cranial modification but also offers a glimpse into a fascinating aspect of a bygone era. As the researchers delve deeper, we can expect to learn more about the social dynamics and cultural significance of this head-shaping practice in ancient China.