Researchers led by Ron Pinhasi from the University of Vienna and Mario Novak from the Institute for Anthropological Research, Zagreb, have unveiled a recent archaeological discovery in Croatia shedding light on a fascinating practice from the past and the complexities of human migration. Their study, published in PLOS ONE, reveals evidence of artificial cranial deformation (ACD) on two skulls dating back to the 5th-6th centuries AD.

The discovery was made at the Hermanov vinograd site in Osijek, Croatia. This location, known since the 19th century, yielded a new excavation pit in 2013 containing the remains of three individuals. These skeletons belonged to the Great Migration Period, a time of significant movement and cultural interaction across Europe.

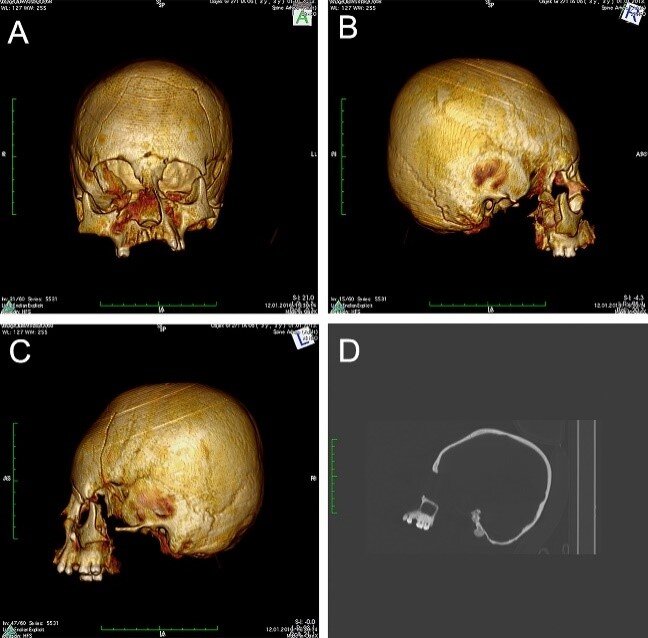

Intriguingly, two of the three skulls displayed dramatically altered shapes. One exhibited an elongated, diagonal shape, while the other was compressed and heightened. This practice, known as ACD, involves intentionally reshaping the skull during infancy, often for reasons related to social status or cultural affiliation.

The study combined diverse analyses – genetic, isotopic, and skeletal – to paint a clearer picture of these individuals. All three were identified as males aged 12-16 at the time of death and showed signs of malnutrition. While no clear differences in social status were evident, a groundbreaking revelation emerged through genetic analysis. The two individuals with modified skulls possessed remarkably distinct ancestries: one with origins linked to the Near East and the other with a majority East Asian ancestry, the first such individual from the Migration Period found in Europe.

The researchers propose that ACD in this instance might have served as a marker of cultural identity during a period of intense interaction between various groups. However, the exact affiliation of these individuals remains unclear; they could have belonged to the Huns, Ostrogoths, or another population. Additionally, the study raises a question about the prevalence of ACD as a cultural marker during this time period. Was it a widespread practice, or specific to these individuals?

Dr. Novak emphasizes the significance of the genetic findings: “The most striking observation is the vast difference in their genetic ancestries. The individual without cranial modification has a broadly West Eurasian ancestry, the one with a circular-erect type deformation has Near Eastern ancestry, and the individual with the elongated skull is of East Asian descent.”

This discovery offers valuable insights into the complexities of human migration and societal dynamics during the Great Migration Period. The use of ACD as a potential marker of cultural identity adds another layer to our understanding of how these diverse groups interacted and potentially distinguished themselves from one another. Further investigations at sites like Hermanov vinograd may unlock more clues about the prevalence and significance of ACD in this historical context.

Source: Public Library of Science