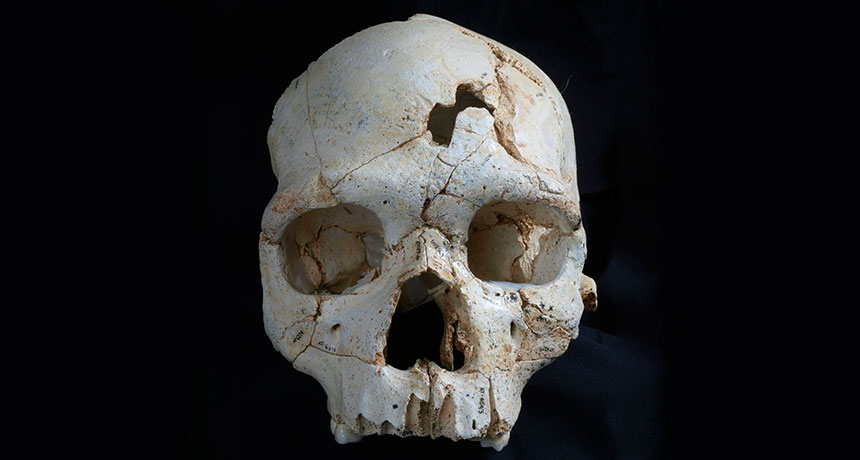

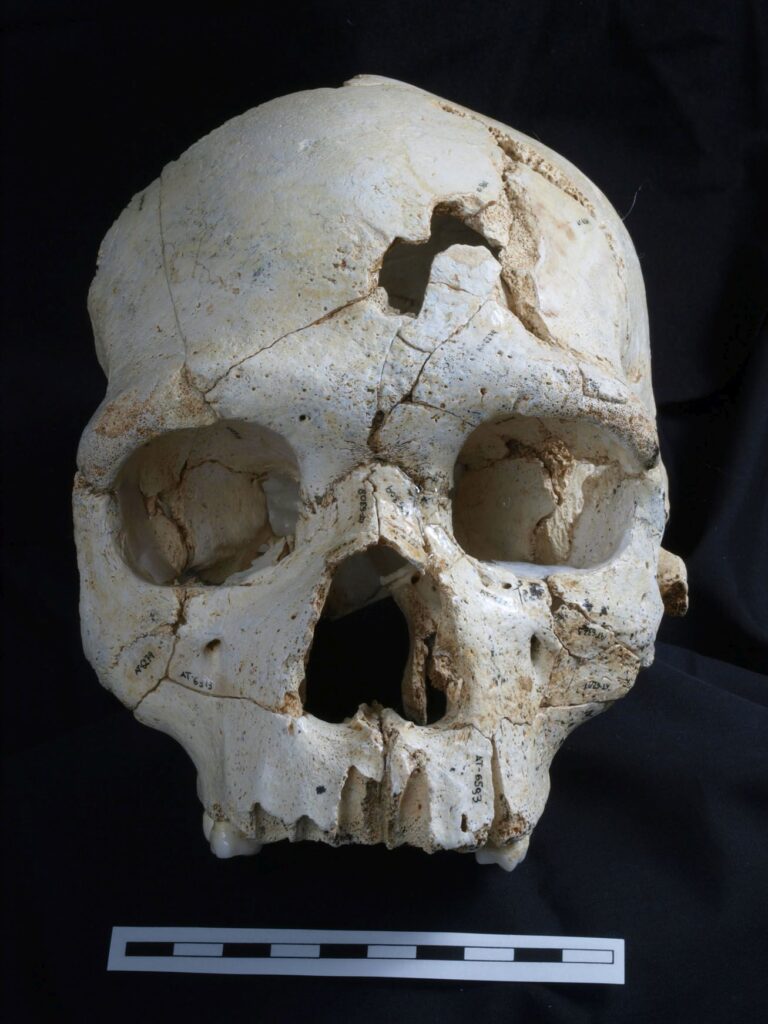

A recent study published in PLOS ONE has ignited a heated debate among archaeologists and anthropologists. The focus? A human skull, nicknamed Cranium 17, unearthed from the enigmatic Sima de los Huesos site in northern Spain. The skull’s unique injuries hint at a potential homicide, raising the possibility of one of the earliest documented cases of murder in human history.

Sima de los Huesos, translating to “Pit of Bones,” is no ordinary archaeological find. Deep within a complex cave system, this Middle Pleistocene treasure trove holds the skeletal remains of at least 28 individuals, dating back a staggering 430,000 years. The only known access to this site is a perilous 13-meter vertical shaft, adding a layer of mystery to how these human remains ended up there.

Cranium 17, meticulously pieced together from 52 fragments over years of excavation, presents a compelling case. The skull exhibits two distinct lesions on the frontal bone, positioned directly above the left eye. Researchers, wielding modern forensic techniques, meticulously analyzed the contours and trajectories of these wounds. Their conclusion: both fractures were likely inflicted by the same object in two separate blows, delivered close to the time of death.

This finding throws a curveball at the theory of an accidental fall. The location, type of fracture, and the apparent use of a single object in deliberate strikes all point towards a more sinister scenario – lethal interpersonal violence. If this interpretation holds true, Cranium 17 could represent the earliest documented evidence of murder ever discovered.

The study delves deeper, suggesting that if the individual was already deceased, the body was likely transported to the top of the vertical shaft by others. This act of transportation strengthens the theory that humans were responsible for the accumulation of bodies in Sima de los Huesos, potentially hinting at early funerary practices.

However, the discovery isn’t without its limitations. The exact cause of death remains shrouded in mystery, and the identity of the potential perpetrator(s) is lost to the sands of time. Despite these limitations, the lethal wounds on Cranium 17 offer a provocative window into a potential dark side of human behavior that might have existed hundreds of thousands of years ago.

The study has sparked a lively debate within the scientific community. Some researchers remain skeptical, arguing that alternative explanations for the skull’s injuries cannot be entirely ruled out. Others, however, see this as a compelling piece of evidence suggesting a capacity for violence in our early ancestors.

Future research at Sima de los Huesos, including a closer examination of other skeletons, may provide further clues to support or refute this theory. The story of Cranium 17 serves as a reminder that the past is a complex and often violent place, and our understanding of human behavior in deep prehistory continues to evolve.

Source: Public Library of Science